History and Summary of the Text by Lori J. Walters

The Roman de la Rose is the work of two authors. Begun by Guillaume de Lorris around 1230 and continued by Jean de Meun approximately forty years later, the Rose is probably the most influential work written in the Old French vernacular. In the centuries following its composition, major poets like Guillaume de Machaut, Jean Froissart, Eustache Deschamps, and Francois Villon continued to write in a tradition dominated by the work which, in some manuscripts, extends to 21,750 lines. In the early 15th century, the Rose was still capable of sparking heated literary debate in France. Other national literatures felt the effect of the Rose as well. The English poets John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer and the Italian poets Dante and Petrarch were astute readers of the work.

The Roman de la Rose is an allegorical love poem which takes the form of a dream vision. The 25-year-old narrator recounts a dream he had approximately five years previously, which has since come to pass. In his dream he journeyed to a walled garden in which he viewed rosebushes in the Fountain of Narcissus. When he went to select his own special blossom, the God of Love shot him with several arrows, leaving him forever enamored of one particular flower. His efforts to obtain the Rose met with little success. A stolen kiss alerted the guardians of the Rose, who then enclosed it behind still stronger fortifications. At the point where Guillaume de Lorris’ poem breaks off, the protagonist, confronted with this new obstacle to the realization of his love, is left lamenting his fate. Jean de Meun concludes the narrative with a bawdy account of the plucking of the Rose, achieved through deception, which is very unlike Guillaume’s idealized conception of the love quest.

The sections of the Rose composed by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun have markedly different characters. Guillaume’s work is a fairly comprehensive handbook on the art of romantic love. The personified likenesses of anti-courtly vices arrayed on the walls of the garden provide an instructive contrast to the figures of courtly virtue who dance within the confines of the enclosure. The God of Love gives specific recommendations to the neophyte on the conduct becoming a lover. In Jean de Meun’s hand, Guillaume’s original plot line concerning a young man’s quest for the Rose is made to encompass a great deal of 13th-century learning. His personified characters (Lady Reason, the Lover, Nature, Genius for example) add lengthy commentary on subjects often allied to the action in only a peripheral way. Among other topics, he includes discussions on free will versus determinism as well as on optics and the influence of heavenly bodies on human behavior. Contemporary issues like the debate about the growing power of the mendicant orders also find their way into his work.

The Manuscripts by Beatrice Radden Keefe

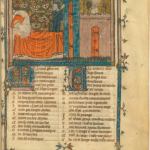

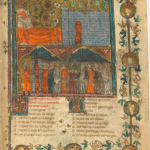

About 320 manuscripts and manuscript fragments containing all or parts of the Rose poem survive. With dates ranging from the 13th to the 16th century, Rose manuscripts are kept mainly in European libraries, and most remain in France where they were first produced. A late 13th-century copy of the poem now held by the BnF is Français 378 (see Figure 1-each thumbnail can be clicked on for a detailed view). Made not long after Jean wrote his continuation, this manuscript includes 40 column miniatures illustrating Guillaume’s section of the poem as well as several prefacing texts. A much later illustrated Roman de la Rose is Morgan 948 in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York (see Figure 2). With 107 single- and double-column miniatures, this deluxe manuscript was produced ca. 1520, after the first editions of the poem were printed at the end of the 15th century (for examples of these, see Rosenwald 396, Figure 3, an incunable, and Rosenwald 917, Figure 4, an early printed book). In the case of Morgan 948, both Guillaume and Jean’s sections of the poem have illustrations.

Many Rose manuscripts are illustrated, some with large cycles of miniatures and lavishly painted with gold and colored pigments. Others are unillustrated or have a single opening illustration and so represent a less costly undertaking (Senshu 2, Figure 5, and Senshu 3 are both unillustrated). In several of these manuscripts, spaces were left for illustrations that were never begun, possibly because their makers ran out of time or funds. (Look at Français 803 for examples of unfinished illustrations, see Figure 6.)

Something is known of the artists responsible for individual Roman de la Rose manuscripts. Professional illuminators Richard de Montbaston and his wife Jeanne (fl. 1325-1353), who lived and worked together on the rue Neuve Notre-Dame in Paris, are thought to have illustrated as many as 20 Rose manuscripts between them, including the Rose in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Walters 143, as well as Français 802 (Figure 7) and Arsenal 3338 (Figure 8) in Paris. Also, miniatures in a Rose now in Oxford (Douce 195, Figure 9) are considered the work of Robinet Testard (fl. 1475-1523), the illuminator of a number of books produced for Charles d’Orléans, count of Angoulême, and his wife Louise de Savoie.

The grandest of Rose manuscripts were made for and owned by noble patrons and members of the French royal court. With 125 miniatures, Douce 195 is thought to have been made especially for Louise de Savoie (1476-1531), the countess of Angoulême and regent queen of France (r. 1515-1516), while the Morgan Rose manuscript was intended as a gift for her son, François I, king of France (r. 1515-1547). We find him being presented the manuscript in the full-page miniature at the beginning of Morgan 948 (folio 4r, see Figure 10). Less costly and unillustrated manuscripts might have been owned by wealthy families or learned individuals such as Christine de Pizan, Jean de Montreuil, the brothers Gontier and Pierre Col, and Jean Gerson, who debated aspects of the poem in the earliest years of the 15th century.

Certain Rose manuscripts are in pristine condition and appear as though they were hardly ever opened and read. But there are also examples of works that were quite clearly often thumbed through and looked at, and many of these now have missing folios, illustrations that are damaged or removed, and notes jotted in their margins. In the Walters Rose manuscript scenes of a Dominican friar with a woman (folio 69v, see Figure 11) and a dog dressed in a Dominican habit and followed by three smaller dogs (folio 72v, see Figure 12) have been added to the lower margins of two folios.

This gives us an idea of the range of ways the poem might have been read and interpreted, and Rose manuscripts used and adapted for different uses, in the late Middle Ages and beyond.